6. Cell Division and the Cell Cycle

- lscole

- Apr 22, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 22

Most of the time, most of your cells are simply doing their jobs. Neurons are sending electrochemical signals. Cardiac muscle cells are contracting rhythmically. Rod and cone cells are detecting the text you're in the process of reading.

At the same time, though, your body is constantly renewing itself at the cellular level. It is estimated that about 330 billion cells in an adult human body are replaced every day (1). That's a big number. But even that represents less than 1% of your cells on that day.

Cell division activity is highly tissue-dependent. Some tissues are high-turnover, meaning their cells divide continuously. These include bone marrow, the lining of the gut, the surface of the skin, and hair follicles--all tissues exposed to constant wear. Cells in other tissues divide rarely or not at all including neurons, cardiac muscle cells and most retinal cells.

In addition to cells in tissues that divide routinely, the body also uses cell division as a repair strategy, replacing cells that have been damaged or that have reached the end of their functional lifespan. Cell division thus serves two purposes: maintenance and repair.

Naturally, cell division is more common when an organism is growing. Embryonic development is dominated by rapid cell division, as the body’s basic form and organs are constructed. By birth, the human body has on the order of a trillion cells—meaning that, at minimum, roughly a trillion cumulative cell divisions must have occurred to build the baby's body from a single fertilized egg. (2) Even after birth, cells divide more frequently in infancy and childhood than in adulthood.

All of this renewal depends on a single recurring process: the cell cycle. In this chapter I'll be reviewing the cell cycle: the sequence of events cells go through when they're dividing.

For actively dividing human cells, this cell cycle takes about 24 hours. By convention, the cell that's dividing is called the "parent cell" and the two resulting cells are called "daughter cells." I'll mention this again: this an a few other gender-related terms used in molecular biology are historical conventions; no biological meaning is attached.

The cell cycle

Let’s begin with a cell that has exited the active cell cycle. Such a cell is said to be in the phase of the cell cycle called G0 ("G zero"). This is a resting phase but one that can be exited into active cell division. Many cells spend most—or all—of their lives in G0, performing their particular specialized function without dividing.

Entry into G1, the first phase of the cell cycle, is usually triggered by external growth signals—proteins released by other cells when new cells are needed. This ensures that cell division is coordinated at the tissue level rather than occurring randomly. There are important exceptions, though. Some stem cells and surface-lining cells—such as those lining the gut or skin—divide more or less continuously, without requiring a signal, while others—such as neurons and cardiac muscle cells—almost never re-enter the cell cycle at all.

For those cells that are prompted by growth factors, those proteins bind to receptors on that cell’s outer membrane, initiating a cascade of protein-based signals inside the cell that ultimately turn on genes required for growth and division.

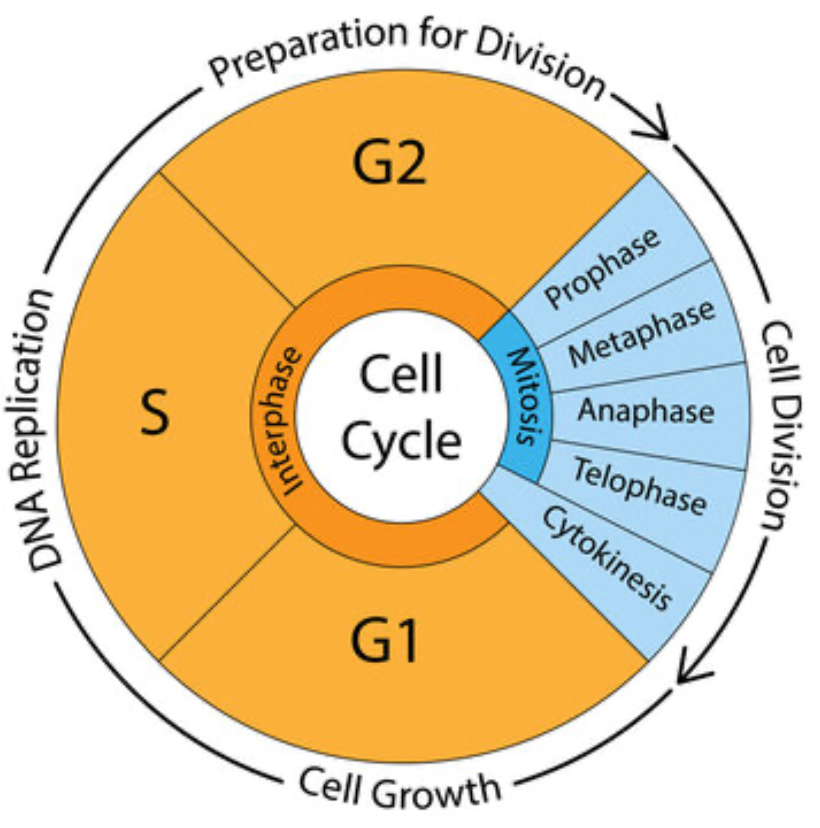

The cell cycle begins in G1 (the first cell growth phase), then enters the S (synthesis) phase where it will replicate its genome, then G2 (a second cell growth phase) before initiating the four steps of M phase (mitosis) where the newly replicated chromosome will be partitioned into the two new cells. By convention, the first three phases (G1, S, and G2) are referred to as "interphase" distinguishing it from M phase (mitosis) where the newly synthesized chromosomes are partitioned into the two new cells. In the last step, cytokinesis, the cell pinches in at its middle and the two new cells separate.

For many rapidly dividing human somatic cells (not sperm or egg cells) under favorable conditions, this cell cycle takes about 24 hours. Let's get a sense of the temporal breakdown before describing each step. These numbers should be thought of as typical, not fixed. Cells stretch or compress the cell cycle—especially G1—depending on circumstances.

But for a typical, rapidly dividing somatic cell (this excludes sperm and egg germ cells) G1, S, and G2 take about 10 hours, 8 hours, and 4 hours, respectively. M phase (mitosis) itself takes about an hour, followed by cytokinesis, which also takes roughly an hour.

Let me briefly cover each phase before discussing how the cell progresses through the cell cycle; how it "knows" when to move from one phase to the next.

G1 phase

The cell cycle starts at G1, the first growth phase. Early biologists saw nothing happening during this phase and so labeled it "G1" for "gap 1." Today we know that it's better labeled "growth 1." In addition to growing, other processes take place during G1. The cell is assessing nutrient availability to make sure it's ready to enter S phase. This is because a major cell cycle checkpoint occurs at the end of G1. At checkpoints, the cell effectively asks whether "all systems are go." A "yes" answer allows the cell to proceed into the next phase.

S phase

The synthesis (S) phase of the cell cycle will be the focus of the entire second half of this book, so I won't say much about it here. Big picture, the cell's task during S phase is to make a copy of its entire DNA genome.

G2 phase

Having synthesized the new genome in S phase the cell now enters G2, the second growth phase. Our target cell will soon be two cells, so it must manufacture more organelles and other cellular components to fill them. That's one of the central tasks of G2. In addition, the cell is repairing any DNA damage or replication errors that might have occurred during S phase. The chromosomes that will be the focus of mitosis must be in near-perfect shape before the cell segregates them. There's another checkpoint at the end of G2 for confirming genome integrity.

Mitosis

At the outset of M phase, the two copies of the parent cell's 46 chromosomes synthesized in S phase exist as long, tangled strings in the nucleus. It's exactly here that we'll pick up the story in the next chapter. But before we do, I want to discuss how the cell moves itself from one phase to the next during the cell cycle.

Regulating the cell cycle: cyclins and CDKs

At each phase of the cell cycle, new sets of genes must be turned on and others off to accomplish the tasks of that phase. Movement through each phase of the cell cycle is accomplished by protein families that will work as partners: cyclins and CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases). These protein families will also figure in our discussion of genome replication. So let's pause here briefly to discuss CDKs and cyclins.

A CDK is a type of enzyme called a kinase. Kinases grab an ATP molecule, remove its last phosphate, and attach it to specific other proteins. In fact, kinases target specific amino acids on the target proteins. The placement of the phosphate must be exact.

Generally speaking, kinase-attached phosphate groups play very important roles in the cell. In some cases, they identify, or flag, a protein as a target for some action by another protein. It might be export out of the nucleus. It might be degradation by another protein.

In other cases, phosphate groups don't serve as flags, rather they're attached to a protein in order to change the conformation (shape) of the protein and thus alter its function. So kinase-attached phosphate molecules are like powerful switches with different purposes depending on the protein and the context.

The cell cycle is driven not by a single master clock, but rather by a series of molecular partnerships. The main players are a family of enzymes I just mentioned that act as molecular switches: CDKs. These CDKs are present in the cell all the time, but they remain inactive unless they bind to a specific partner cyclin. In other words, CDKs are machines wandering around waiting for the right key.

Different cyclins are expressed at different stages of the cell cycle. When a particular cyclin is produced, it binds to its partner CDK and switches it on. The activated CDK then phosphorylates many other target proteins, triggering the events required for that phase of the cycle.

As one phase ends, its cyclin is destroyed and replaced by another, activating a new set of CDKs and moving the cell forward through the cell cycle. One simplified example will give you the flavor. The point of this illustration is not to memorize which cyclin is active in each phase. It's to see how the cell keeps time—not with a clock, but with a carefully choreographed sequence of molecular activations.

Our illustration starts at the outset of G1 phase. Cyclin D activates its partner CDKs, which in turn activate genes required for cell growth and commitment to the cell cycle. As the cell approaches the G1/S transition, cyclin E takes over, activating CDKs that prepare the cell to begin copying its genome. During S phase, cyclin A attaches to other CDKs and that drives DNA replication. Later, in G2 and M phase, cyclin A and cyclin B activate other CDKs that carry the cell through mitosis and prepare it for cytokinesis, or cell division.

The molecular details of which cyclins and which CDKs are involved differ from phase to phase, but the underlying logic is the same throughout the cycle: changing cyclins activate specific CDKs, and those CDKs push the cell effectively irreversibly into the next stage.

Timing matters because copying a genome and dividing a cell are two of the most dangerous things a cell ever does—and nearly every major failure of cell regulation, including many forms of cancer, traces back to mistakes made here.

Before we continue, I want to mention that all of the cellular processes I'll soon be describing are carried out by proteins and complexes that have scientific names. I'll occasionally mention those names, but my focus will be on what these molecular machines do rather than what they're called. This holds for the rest of the book, too.

To catch ourselves up here, the first three phases of the cell cycle are the preparation phases—the copying of the genome, the checking of the work, and the setting of the stage for division. In the next chapter, we cover the fourth and last phase of the cell cycle, mitosis, in which the chromosomes are partitioned into two new cells that then bud off from the initial cell. It's an absolutely amazing process that I'll be likening to a line dance.

(1) Scientific American, April 1, 2001, Our Bodies Replace Billions of Cells Every Day. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/our-bodies-replace-billions-of-cells-every-day/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

(2) Bionumbers. Accessed 1-15-2025. https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?id=106413&ver=4&utm_source=chatgpt.com

Comments