4. Tiny Machines

- lscole

- Apr 9, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 22

Let's first get some perspective. Proteins account for about 50% of the cell's dry weight. That's much more than DNA, which accounts for about 1-2%. It's also more than RNA, which accounts for approximately 20%. All of these figures depend on cell type and growth state. But--big picture--about half of the cell is proteins.

But it isn't just the quantity that makes them important. Proteins are the workhorses of the cell. RNAs play key functional roles in the cell, too. But even when RNAs act directly, they usually do so as part of protein-RNA machines. To keep our model of the cell a bit simpler, we'll focus only on proteins.

Categorizing Proteins

In this book, I'll be categorizing proteins in two different ways. The first and most important is based on the protein's purpose: some proteins play functional roles (they do things in the cell) and others play structural roles (they physically support things in the cell).

The best-known functional proteins are enzymes--proteins that speed up chemical reactions. But there are other kinds, including signaling proteins, receptors, transcription factors and transport proteins, all of which I'll talk about. Think of the structural proteins as building materials. They provide mechanical support to the cell overall and scaffold organelles. But they, too, are dynamic and regulated.

The second protein categorization scheme is based on shape. Many proteins have a roughly round or irregular shape. These are globular proteins. Most, but not all, are functional. Other proteins are longer and more cable-like. These are called fibrous proteins and most, but not all, play structural roles.

Back to perspective. It's not just that the amount of protein in a cell that's impressive. And it's not just the fact that they're the cell's "do-ers." It's also impressive that human cells have the ability to express tens of thousands of different proteins, each with a unique three-dimensional shape. Much of the diversity of proteins is due to the many kinds of functional proteins. There are very roughly about ten times as many kinds of functional proteins as structural proteins.

In the cell analogy I used in the previous chapter, I likened functional proteins in a cell to workers in a factory. But how do proteins do their jobs? It's simple: it's based primarily on shape. I think it's safe to say that the majority of what happens in a cell relies on molecular shape. Proteins don't use words. Their language is shape. I'll return to this point in a bit.

Diverse Kinds of Functional Proteins

Below are examples of diverse functional proteins doing their jobs. Note the importance of shape in each example.

Enzymes: Some globular proteins have a nook that a specific smaller molecule fits into that facilitates a specific chemical change to that molecule. Enzymes aerep roteins that speed up chemical reactions. For example, in the very first step in glycolysis (the breakdown of glucose) the enzyme hexokinase transfers a phosphate group to a glucose molecule. That's all it does. But it does it well!

Signaling proteins: There are also signaling proteins. These proteins typically travel in the blood and attach to receptors (also proteins) on the surface of specific cells to, in effect, "tell" them to behave in a certain way. For example, insulin is a protein hormone produced by the pancreas. It travels in the blood then attaches to cellular receptors, signaling them to absorb glucose.

Motor proteins. Imagine a fibrous protein capable of pulling itself along a second fibrous protein to effect movement. This is what the motor protein myosin, and its partner protein actin do. As many myosin-actin complexes in voluntary muscle cells slide along each other in a contracting motion causing muscle fibers to contract at the macro level. We'll be looking at this in detail in a later chapter.

Transport proteins: Other proteins are involved in transporting nutrients and other molecules around the body. For example, hemoglobin proteins floating freely in the blood carry oxygen molecules to every part of the body. Other transport proteins carry specific molecules through the cell membrane either into or out of the cell.

Transcription factors: Genes coded in our DNA provide the information (shape) needed to make proteins. But there's a bit of a circularity here because it is proteins that turn genes "on." Proteins that attach to DNA near a gene's starting point and activate transcription (usage) of that gene are called transcription factors. We'll cover transcription soon. For now just be aware that it kicks off protein synthesis inside the cell.

Carrier proteins: Another kind of transport protein works inside the cell carrying large structures. One of these proteins is kinesin. Kinesin literally walks (yes, it has two "legs") along stretches of long microtubules (components of the cytoskeleton) carrying large vesicles, organelles, and molecular complexes to other parts of the cell where they are needed. Here's an animation showing a kinesin protein carrying a vesicle.

As you can see, taken as a group, proteins perform diverse jobs in the cell. But each individual protein performs a very specific job (or very small number of jobs).

Proteins are Chains of Amino Acids

How does the cell create thousands of different protein machines? Efficiently! Proteins are built from just 20 different smaller subcomponent parts called amino acids. Amino acids are all chemically different from each other, but they are similar in that they all capable of attaching to each other in linear fashion. On average, a human protein might be composed of 300-400 lined up and connected amino acids. But proteins can range from 50 to thousands of amino acids long.

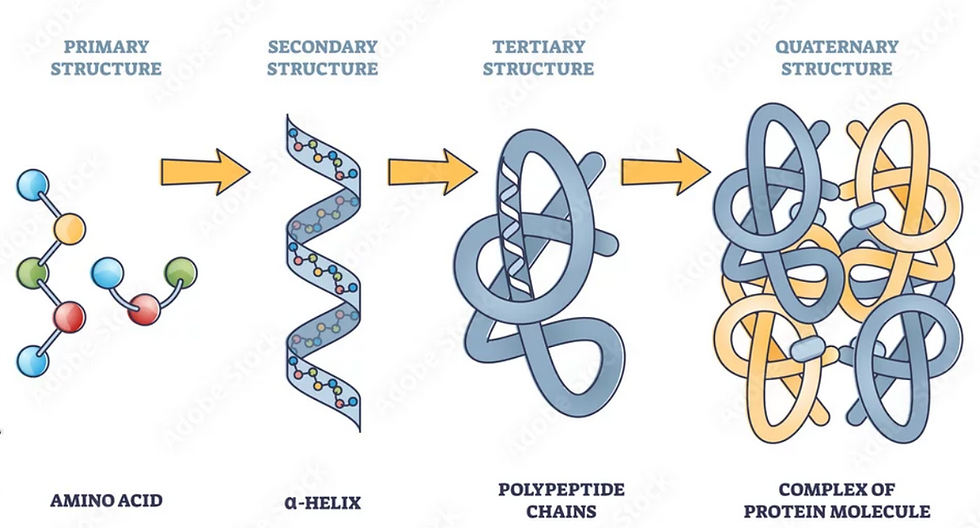

Think of 20 differently colored beads threaded on a string. Any number of beads can be on the string in any order. Each of the differently colored beads represents a different amino acid. So stringing the beads is a bit like creating a polypeptide, or protein. At its most basic, a protein is a linear stretch of amino acids. That's it. We call the protein's linear order of amino acids its primary structure.

In the previous paragraph, I used the term "polypeptide." The attachments between amino acids are called peptide bonds. Another term that's used in discussing proteins is "polypeptide," meaning "many peptide bonds." A polypeptide is simply a linear chain of amino acids. It doesn't yet function as it ultimately will once it folds. So, a "protein" is a polypeptide, but one that has folded on itself and is now functional.

From Chains to Tiny Machines

Importantly, different amino acids have different chemical properties. Some are positively charged; others are negatively charged. Some are large; others are small. Some are hydrophilic (attracted to water); others are hydrophobic (repelled by water). Thus, each of the 20 amino acids responds to other amino acids in their environment differently. Because of all the attractions and repulsions between different amino acids in the chain, linear protein molecules fold into precise three-dimensional structures.

Early in folding, two common three-dimensional secondary structures appear: alpha helices (a single helix, not a double helix) and beta pleated sheets (where a run of amino acids forms switchbacks with itself). Don't worry about the names. The point is that in a water-based milieu, the linear array of amino acids will tend to quickly fold into two common three-dimensional structures (secondary structures). Neither of these secondary structure are required to be present in a given protein. But one or more of both usually are.

After or while the alpha helices and beta pleated sheets form, the protein folds on itself in other ways so that these two kinds of secondary structures get positioned within the larger folded structure. This is referred to as the protein's tertiary structure. This is the functional three-dimensional form of the proteins--the form capable of doing jobs like serving as enzymes, signaling, carrying molecules, contracting muscles, and turning on genes.

Multi-Protein Complexes

Finally, in some cases, multiple folded polypeptide chains (i.e., proteins) assemble to form a multi-protein complex. When more than one protein combines into a functional complex, the complex is an example of quaternary structure. Quaternary structures can contain two, three, four, or five proteins and those would be referred to as "dimers," "trimers," "tetramers," and "pentamers," respectively.

The oxygen-carrying hemoglobin molecule I mentioned earlier is a tetramer comprised of two copies of two different polypeptides known as its alpha and beta chains (not to be confused with alpha helices and beta pleated sheets). Each of the four polypeptides can deliver one oxygen molecule, but only in the context of a tetramer complex.

OK. That's a quick introduction to proteins. As we get farther into our discussion of genome replication, we'll see that innumerable functional proteins play the leading roles. But first, let's talk about DNA.

Comments